“The surest path to safe streets and peaceful communities is not more police and prisons, but ecologically sound economic development. And the same path can lift us to a new, green economy – one with power to lift people out of poverty while respecting and repairing the environment.”

-Van Jones

Founder, Green for All

Last week (20th Nov 2018 to 29th Nov 2018), CLTS Foundation joined hands with Vita, an Irish NGO to commit to the cause of contributing to Ethiopia’s strategy to improve efficiency of biomass use which plays a major role in Ethiopia’s vision of becoming a middle-income country with a Climate-Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) by 2025.

The World Energy Council defines biomass as sources of energy that is being derived from organic matter provided that they are not embedded in geological formations, i.e., fossilized. Traditional forms of biomass imply forestry and agricultural residues. Data from The World Energy Council reveals that woody biomass is the source of over 10% of all energy supplied annually in the primary energy supply of forest biomass used worldwide. Overall, woody biomass provides about 90% of the primary energy annually sourced from all forms of biomass. About 90% of all the biomass consumption is in the traditional use. The major use of biomass (two-thirds) is in the form of cooking and heating in rural areas of developing countries

Ethiopia has identified Water and Energy to be the key to achieving its goals for CRGE and poverty eradication. Amongst several other implications for the Water and Energy sector’s contribution to Ethiopia’s development, it is alarming to note that by 2030, fuelwood availability in the country will be severely impacted by an increase in temperature and changes in rainfall patterns. The fuelwood final consumption in Ethiopia in the year 2017 was 82,853 thousand cubic meters and the country has already shown a rapid decline in forest cover from 15.2% in the year 1990 to 12.5% in the year 2015 (World Bank, 2015). With the current trend of declining forest cover and ever-growing demand for fuelwood, it has been estimated that up to 8.5 million people will be living in high-risk areas in Ethiopia where they are unable to meet their household energy needs. Hence, it can be stated with conviction that there is a dire need for efficient utilization of the available woody biomass and serious alarm needs to be raised not only on the sustainability of the current conservation, management and forms of collection and consumption of fuelwood but regeneration and creation of biomass and afforestation.

The current strategic priority of Ethiopia for sustainable access to energy under CRGE focuses on improved efficiency of biomass use; in other words, working towards reducing the demand for biomass by increasing fuel efficiency. The traditional cookstoves (Sost Gulicha in Amharic) are the commonly used cookstoves by the Ethiopian rural community. The fuel (charcoal, firewood) used in these do not undergo complete combustion and hence leads to inefficient usage of the resource and excessive demand for fuelwood. Smoke from the traditional cookstoves is a major cause of indoor air pollution and directly impacts the respiratory health of the women and children in particular. It is also dangerous since there is no covering surrounding the fire and can lead to fire hazard and burns. Indiscriminate and widespread collection of fuelwood is also a major cause of deforestation and degradation of the natural environment leading to soil erosion, loss of biodiversity among other impacts.

The National Improved Cook Stoves Programme (NICSP) designed for this purpose has the goal of distributing 30 million improved cookstoves (Gonzeye, Mirt, Opessi and Tikikil) by 2031 and also linking second order benefits such as reduced emissions, deforestation, dam siltation. This would, of course, catalyse a massive positive health impact on millions of rural women, who would be able to protect themselves from respiratory disorders from directly inhaling smoke while cooking in traditional stoves. (Picture of Mirt model of cook stove on left)

The objective of CLTS Foundation’s mission was:-

- To explore and identify how the community led approach can be utilised for mobilising communities to adopt fuel-efficient cookstoves.

- To agree on a framework for a new community-based approach to adoption of fuel-efficient cookstoves (Community Led Approach to Fuel-Efficient Cook Stoves).

- To identify what agencies will take part in the pilot programme and what their roles and responsibilities would be and get a commitment from stakeholders.

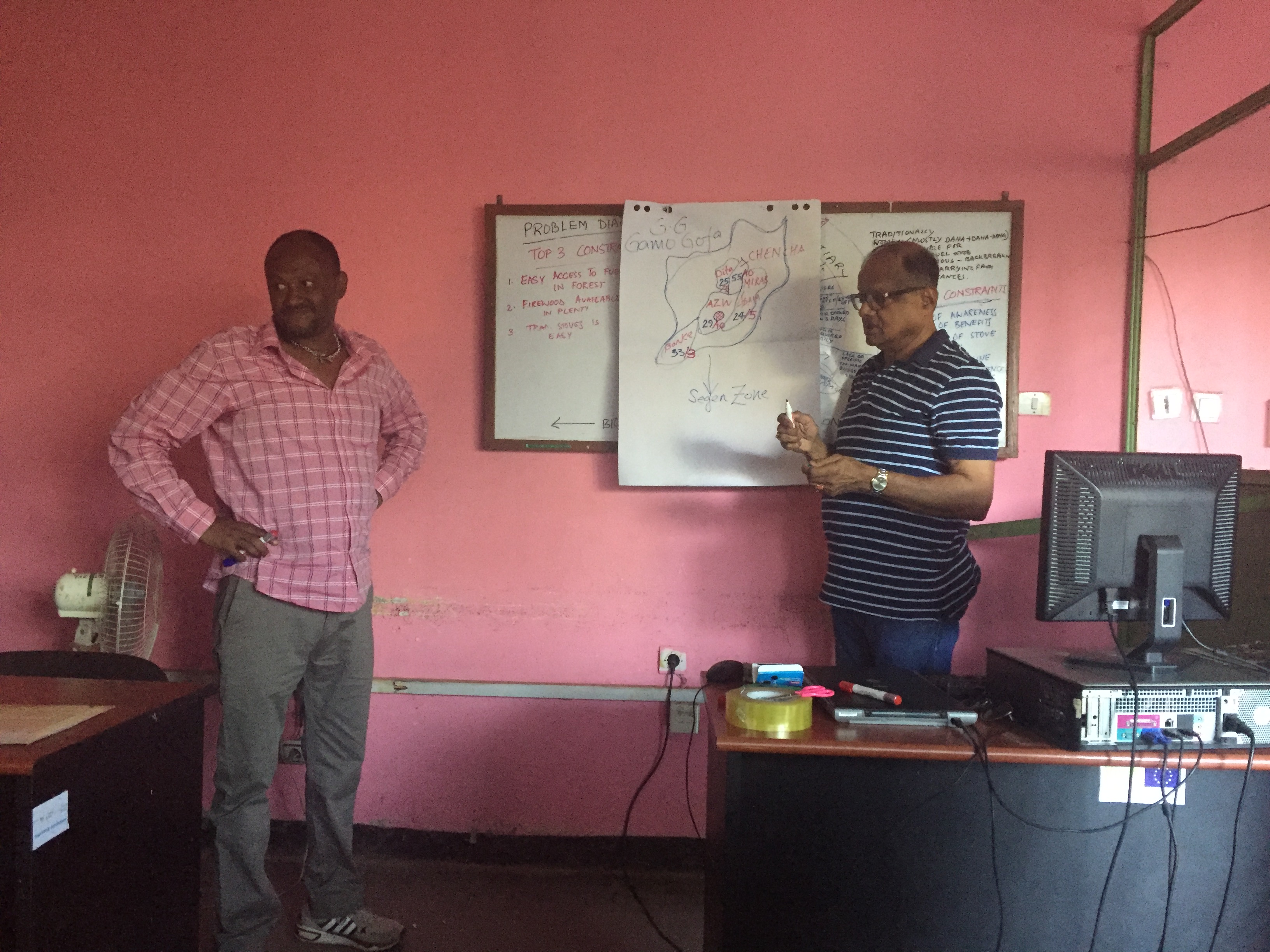

In order to do so, the CLTS Foundation team embarked on a week-long mission in Ethiopia in the last week of November 2018 involving extensive field visits, workshops, discussion and brain-storming sessions with Vita. We were first briefed about the targets and roadmaps in place for faster achievement of fuel-efficient cookstoves. Discussions were held on the availability of improved models of fuel-efficient cookstoves, community preferences of the models and technical issues. Initial participatory exercises with Vita team members revealed the bottlenecks leading to slow adoption of fuel-efficient cookstoves and consensus was reached on the top three biophysical and socio-economic factors that contributed to the slow pace of uptake.

Next up, we tried to zero in on the kebeles (villages) where we would be applying the CLTS methodology to field test our assumptions in the discussions (Picture on the right). Two villages, Molle in Mirab Abaya woreda and Delbo in Arba Minch Zuriya woreda were chosen. The two villages were distinct in terms where Molle had a higher rate of adoption of fuel-efficient cookstoves amounting to 57% and Delbo had a significantly lower rate of 30%. The villages had a common history of introduction and adoption of CLTS and had achieved ODF status through the approach. We also visited one of the local suppliers who produce the fuel-efficient cookstove ‘Mirt’ model which is the most widely used and accredited model of fuel-efficient cook stove developed in Ethiopia. This was initiated in order to understand the bottlenecks on the supply side.

- Applying the CLTS methodology of triggering (picture on the right) in the two villages brought out a host of outcomes: natural leaders from within the community came forward to form a committee of their own to raise awareness and promote the uptake of fuel-efficient cookstoves in their kebeles.

- The committee got together to chart out a plan on how they intend to achieve a 100% traditional cookstove free kebeles.

- The community members along with the supplier were subsequently invited to participate in the workshop in Hawassa (Head Quarter of SNNP Region), which had participants from various governmental departments, non-governmental organisations, members of the Irish Aid consortium apart from Vita and CLTS Foundation team members.

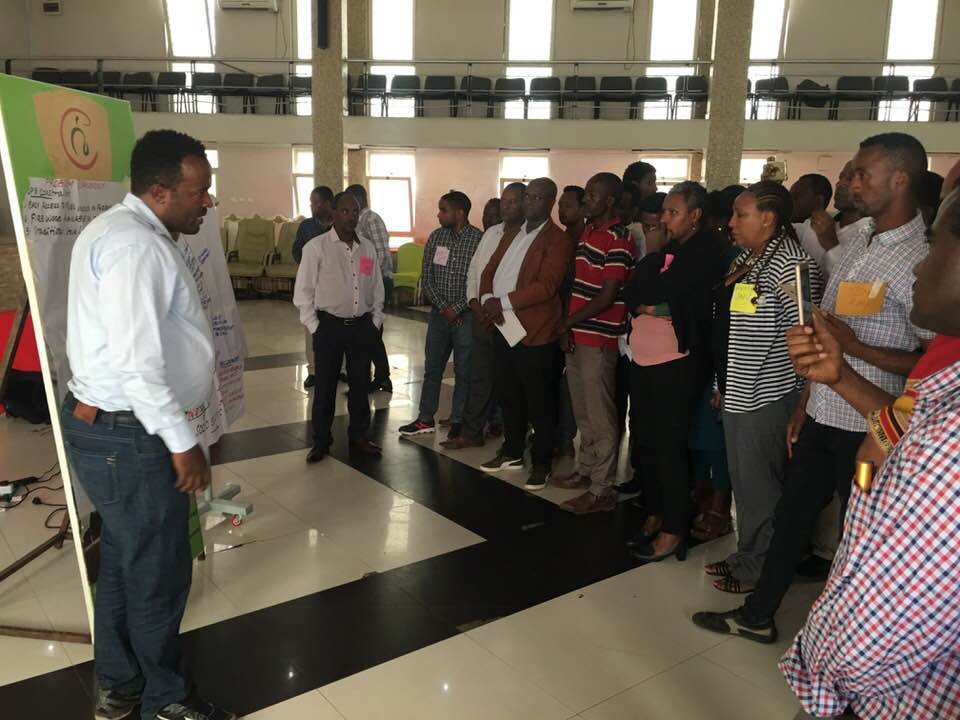

The workshop (on the left) aimed to present the community-led methodology to the participants and to gather their reviews on whether it can be a replicable methodology for the initial pilot project to improve uptake of fuel-efficient cookstoves. Audio-visuals of field exercises were used, community presentations of their analysis of fuel use and secondary data on the effectiveness of this method in the water and sanitation sector were used to capture what was done in the field.

The workshop (on the left) aimed to present the community-led methodology to the participants and to gather their reviews on whether it can be a replicable methodology for the initial pilot project to improve uptake of fuel-efficient cookstoves. Audio-visuals of field exercises were used, community presentations of their analysis of fuel use and secondary data on the effectiveness of this method in the water and sanitation sector were used to capture what was done in the field.

What was rewarding from the entire mission was that participants from diverse institutions expressed their interest in the methodology and were intent on delving deeper into it by trying them in selected kebeles, which had a different contextual setting than the first two. The mission was concluded with key institutional players making a commitment to make at least 20 kebeles to be ‘Sost Gulicha Free’ (Traditional Cook Stove Free) and work towards reinforcing the forward linkages in the supply side and urgently bridging the gap between demand in villages and undisposed stockpile of thousands of improved cookstoves at the end of the producer/supplier through Post-Triggering Follow-up activities. One such activity that was proposed to bridge the demand and supply gap involved increasing accessibility of the fuel-efficient cookstoves where trucks loaded with the stoves can be brought to the villages and it can move around the kebeles supplying stoves to the households that have demanded it. It would function as a ‘limited period offer’ provided that there has been significant demand for the stoves (by at least 50 households) from the kebeles. The institutional actors along with the kebeles committees formed through triggering play a major role here for coordinating the logistics and to make it a successful follow-up activity.

Keep following this space for more updates on how we developed the methodology and why CLTS was piggybacked for the project.

Dear CLTS foundation experts and founder many thanks! what we ignited in those two villages able to manage a good way forward to realising less smoky village. A shifts in attitude is a big achieved.