“Close to 50% of malnutrition around the world is caused not by lack of food or poor diets, but due to poor water, poor sanitation facilities and unhygienic practices”- UNICEF, 2017

The innumerable number of man-days are invested in growing food before it is consumed. It is a general notion that the chain of efforts for producing food including cultivation, harvesting, processing, marketing ends finally at consumption. However, the phase after consumption is of no less importance and greatly impacts the final outcome of the long process involved in food production. This phase is ‘assimilation’ and it is grossly overlooked. In India and in other developing countries where agriculture is the backbone of the rural economy, it is extremely important that this last segment of the food production chain is set right if the health of the millions living in the rural agrarian and urban poor society is to benefit.

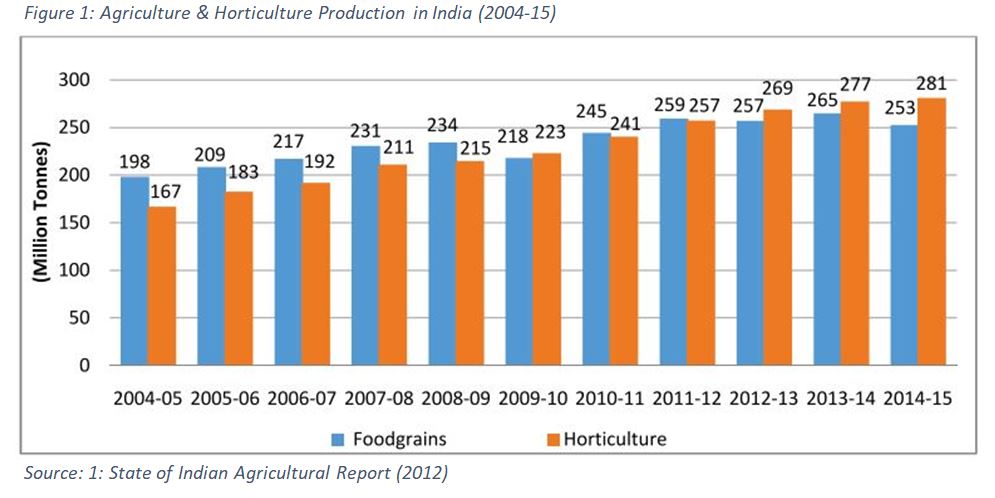

India has achieved greatly in terms of food security since its independence in 1947. India has rapidly enhanced her total food grain production and moved from being a begging bowl to a

bread basket. The agriculture production of our country has risen from 35 million tonnes in 1947 to over 281 million tonnes in 2014-15 with a likelihood of a record 275 million tonnes in 2018 (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2015). While India has achieved greatly in innovative practices of agriculture, the nutrition-availability and stunting status remain dismal. Recent statistics show that stunting levels of our rural population are much more than our neighbouring countries viz. Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan.

bread basket. The agriculture production of our country has risen from 35 million tonnes in 1947 to over 281 million tonnes in 2014-15 with a likelihood of a record 275 million tonnes in 2018 (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2015). While India has achieved greatly in innovative practices of agriculture, the nutrition-availability and stunting status remain dismal. Recent statistics show that stunting levels of our rural population are much more than our neighbouring countries viz. Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan.

This points towards the failure of our compartmentalised focus on different segments of agricultural production right through consumption to assimilation. While crop scientists and agronomists are more concerned about enhancing food production in the shortest possible time, the specialist involved in processing attach more importance to the technological efficiency of processing with minimum degradation of food nutrients and quality.

At the national level, the sector that deals with agricultural production are looked after by the Ministry of Agriculture. The responsibilities of the Ministry begins with making seed and other inputs of agriculture available to farming communities, keeping track of harvesting, collecting and marketing the grains to the markets domestically and globally. However, it is the Ministry of Rural Development that looks after the sanitation and infrastructure development in rural areas with land administration under the purview of the Revenue department. Further, the health and well-being of mothers and children are the responsibility of a separate Ministry of Health. The Ministry in turn mainly focuses on supplying food additives, infusion of nutrients in food and all other aspects of maternal well-being and child growth. It is easy to recognise the compartmentalised approach in which our rural areas are being handled. It is owing to this absence of convergence, that the cross-cutting issue of sanitation continues to remain either neglected or not given as much value by the community as it requires.

In the era of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), this inter-agency coordination has emerged as a moot point of discussion. Presently different government departments, ministries, NGOs, researchers, development professionals and private sector are more focused on achieving SDGs of their respective focus areas. However, if SDGs are to be achieved and the status of nutrition be developed, there is a necessity of convergence of actions that reflect an interaction of goals. The SDG 17 finds immense relevance in this context as it calls for ‘policy coherence for sustainable development’ as a fundamental means of implementation.

While it is incomplete to discuss mitigating hunger, achieving food security or well-being without addressing nutrition, it makes little sense to discuss nutrition in isolation to SDG 3 that talks about health.

It reflects that discussion about nutrition must encompass the wider process of achieving sustainable development. Further, it should also be noted that actions and investments in nutrition have the potential to have a spectrum of impacts in a universal and integrated way. We must appreciate that improved nutrition does not operate in the vacuum but as a part of a larger SDG machine.

However, it is important for us to be mindful of the fact that along with the possibilities of benefits, there is also a potential for incoherence. This would mean that interaction between targets might create situations where the achievement of one inhibits the other. Also, achievement of a particular SDG may not have positive impacts on the other. However, all these SDGs are connected, and it is upon the intelligentsia and policymakers to understand the necessity to deal with these transparently so that they can be leveraged and mitigated. It would serve well if these connections could be mapped to understand the areas of synergies, contradictions, trade-offs and negotiations.

However, sketching correlations and causes between nutrition and other development issues might be complex and part of a larger exercise with widespread ramifications. The fact that no country has been able to come up with an integrated SDG plan, showcasing the difficulty in mapping the relationships between all SDGs. It would serve well to identify the areas of development – in low, middle and high-income countries – across the SDGs in which nutrition can bring real benefits, and where nutrition will benefit from the greater action.

A case in hand could be the SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation that concerns with well-functioning systems of infrastructure with adequate people’s participation. It may be seen that improved nutrition supports this infrastructure by ensuring there is enough ‘grey-matter infrastructure’ i.e. healthy people with knowledge, ability and energy to drive economic development and build the future.

It may be noted that more than 5,00,000 children die of malnutrition every year in India. According to the Global Nutrition Report, of a total of 122 million children under five in the country, over 15 per cent come under the wasting category and close to 38 per cent are stunted. Stunting has a direct correlation with malnutrition. It is also understood that close to 50% of malnutrition is caused not by a lack of food or poor diets, but due to poor water, poor sanitation facilities and unhygienic practices – like not washing hands properly with soap. 2.5 billion cases of diarrhoea in children under-five are recorded worldwide every year, and in India diarrhoea caused an estimated 1,36,000 child deaths in 2012 alone. High population density, lack of sanitation facilities and practice of open defecation stunts children through both loss of food and the reduced absorption of nutrients.

Beyond a plethora of enteric diseases and the subsequent loss of nutrients, open defecation has bearing on repeated faecally-transmitted infections (FTIs) that damage the gut. These FTIs deplete the absorption of vital nutrients that also cause chronic under-nutrition and stunting. Diarrhoea – the most visible and measured of these FTIs – is thought to be just the tip of the iceberg of illnesses.

India has the highest number of people defecating in the open. According to the JMP report of the UNICEF (2015), almost 40% of its total population practices open defecation. In its rural areas, about 56% of people continue to defecate in the open. Poor sanitation services and continuing behaviour of defecating in the open is affecting millions of people, contaminating the environment and practically forcing people to consume each other’s faeces. This has caused the perpetual condition of gastrointestinal disorders hampering efficient absorption of nutrients through digestion. As a result, unabsorbed nutrient passes out through the gastrointestinal tract, depriving the consumer of the benefit of the massive boost in agricultural production that has been achieved by the nation since independence. It must be noted that a sea change can be brought in nutrient absorption of the human body by breaking this chain of faecal-oral contamination by empowering the local communities to analyse their own environmental sanitation and initiate collective local action.

In a recent study conducted in Mali, it was found that the stunting rate of Open Defecation Free villages was comparatively lesser than the villages where open defecation prevailed. It was revealed that stunting in children had reduced by 13% with 26% reduction in severe stunting for children under-five years of age in CLTS villages compared to control villages. There was also a 15% reduction in underweight and 35% reduction in the severe underweight category of children. With regards to diarrhoeal diseases, there was a reduction of around4. 57% under-five mortality in CLTS villages.

For a long time, policy-makers have missed the ‘blind spot’ in nutrition by not better connecting the dots to stunting in India and the widespread practice of open defecation. This has serious implications for how India should be tackling open defecation – by better-combining nutrition and health, to sanitation interventions. In his recent addresses, our Prime Minister has urged states to consider setting up ‘Nutrition Missions’ with an aim to give the problem of malnutrition higher priority and facilitate a coordinated effort by several ministries who are involved.

Now the bigger question remains- Is it possible for countries to strike a harmony and converge the focus of different interventions to a common platform so that the interventions result into tangible health outcomes- i.e. enhanced nutrition?

All other factors remaining same, just by ensuring an ODF environment and eliminating the faecal-oral contamination, a significant nutrition absorption can be ensured. The challenge now is to bring the institutions to work more harmoniously keeping the focus on the shared cause of health outcome and not in isolation of each other.

Leave A Comment